Anabel Sanchez

Online Editor

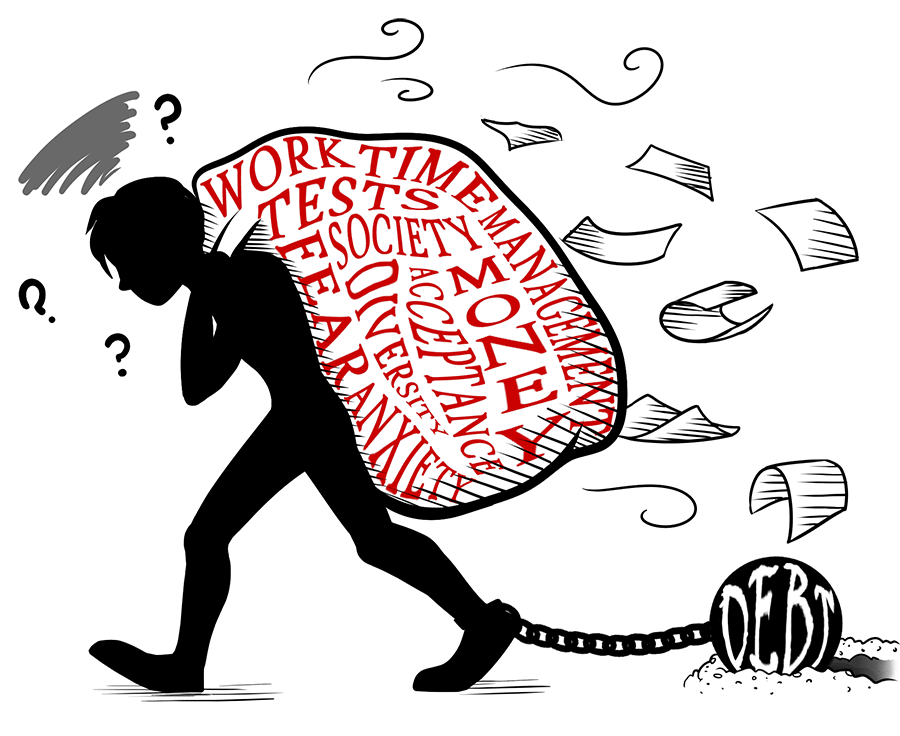

Underemployment, student debt, dropouts, decreased funding, school closures, stagnation and prison systems. What do these key phrases have in common?

Simply the fact that they can all be recognized as elements that are rendering the educational system of the U.S. as one of the most declining systems for a developed country in the world.

Like the strands of a fragile and dangerous spider’s web, the fractures in the system continue to be woven, with the effects growing ever crippling and trapping victims in the process.

According to the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment, which estimates student performance, the U.S. placed 38th in a ranking of 71 countries in which 15-year-olds worldwide had their proficiency levels in math, science and other skills evaluated.

It’s a concerning position to be in when the U.S. is considered a top player in the first-world tier of countries that exist in the world. And yet the U.S. doesn’t even scrape in on the top ten list of most developed countries in the world, according to UN Human Development Data. Norway takes that honor.

Now, let’s run down the list of glaring issues.

School closures. Nationwide school doors are closing due to a lack of funding and poor student body performance. Add overcrowding and teachers in several states battling for better wages to the point of going on strike and you have a situation in which students are having a harder time accessing schools near them.

In fact, the New York Times reported that New York City alone was closing 91 schools in all its boroughs since 2010 due to low performance—an effort that is still playing out today. But, if there’s a widespread low performance, then there must be a root cause.

BC assistant professor of history Rudy Jean-Bart says that reaching out and flexibility is key.

“Education hasn’t mastered adaptability,” he said. “It’s essentially been, this is who we are, take it or leave it. Students feel that school isn’t suited to them and they become labeled as failures. That’s why it’s important for us as instructors to reach out and adapt to our students’ needs, even if it’s uncomfortable for us so that our students can realize their brilliance.”

Whether it’s students’ learning styles having evolved or teachers’ instruction methods becoming poorly outdated, it’s vital for school systems to be up to date with technology and implement the aspects that will better work with young students.

It also isn’t a coincidence that the one thing most of these school closures have in common is that most are happening in urban districts. Students in urban districts often deal with a variety of socioeconomic issues that discourage them and affect their performance down to the way in which they engage.

“They often don’t get taught proper reasoning skills,” Jean-Bart said. “The lack of intellectual engagement that happens makes them ill-prepared for intellectual conversation outside of the classroom. They don’t know what to do with that.”

There’s also a little-discussed issue that has to do with the correlation between the prison system and education.

The U.S. ranks number one in the world with the highest prison population at 655 prisoners per 100,000 people. Among those prisoners are dropouts, many of whom are minorities, who fell through the cracks due to socioeconomic reasons or lack of support at home.

When they are released, they are more likely to return to jail. In fact, Vox.com reported that 76 percent of all inmates end up back in jail within five years of their release. And The National Reentry Resource Center reports that only half of imprisoned adults have a high school degree or an equivalent.

The harsh reality is that employers are less likely to hire former convicts, prisoners often have nothing to return to when released and many deal with a psychological sense of inferiority that inhibits them from embracing education again.

The bridge between those who gave up on education and the education system itself needs to be reconstructed, whether it be through organized reentry programs or awareness efforts.

Then, there is college student debt, which, in the U.S, has now clocked in at a staggering $1.6 trillion. In January 2019, the Sun-Sentinel reported that in Florida alone, student loan debt increased to $89.4 billion from 2015 to 2018.

While at a hearing at Capitol Hill on Sept. 10 regarding the student debt crisis, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez paid $1,200 on her student loans, of which she still has $19,000 left to pay off.

Popular comedian Hasan Minhaj, who was also in attendance, passionately spoke to the committee saying, “Two-thirds of all jobs in America require at least some college. This is the standard now. That wasn’t the case when most members of this committee were in school.”

He went on to add, “Today, the average tuition at all of your schools is almost $25,000. That’s a 110 percent increase over a period of time when wages have gone up only 16 percent.”

Ultimately, one can’t help but wonder when getting a good post-secondary education suddenly meant becoming a slave to years of crippling debt. It’s as if higher education is no longer an institution but a corporation.

Lastly, underemployment post-graduation is a real thing.

According to data from the University of Washington, about 53 percent of graduates are employed at a non-degree required job or remain unemployed. Meanwhile, the Wall Street Journal stated that about 43 percent of graduates overall are underemployed in their first job.

If that degree you’re working so hard for doesn’t equate to the pay or even land you a job, to begin with, then what are you doing this for? Underemployment certainly doesn’t help you in paying off the student debt that will be looming over you like the grim reaper, post-graduation.

And the list of issues goes on.

But it’s important for us to know that this is the reality of what we, as degree-seeking students, face. Hopefully, with that knowledge, we can argue for a change or at least prepare ourselves for the struggle.

Regardless, as we push our brains to the limit trying to achieve our dreams, one thing is certain. The spider’s web keeps being knitted. And no one has found a way to stop it.

sancha9@mail.broward.edu